27 years after Ken Saro-Wiwa’s death, the environment fight goes on

Angela Cobbinah talks to a comrade of the author executed in the struggle against big oil interests destroying their homeland

Friday, 14th October 2022 — By Angela Cobbinah

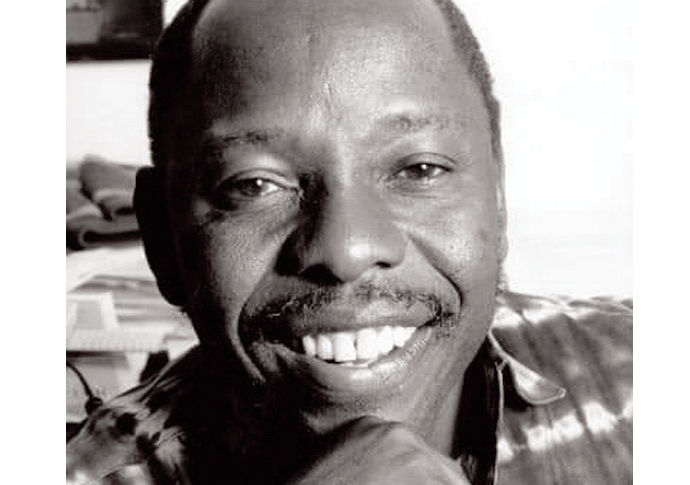

Ken Saro-Wiwa was convicted and executed in 1995 on trumped-up murder charges after leading protests against pollution

NEXT month is the 27th anniversary of the execution of Nigerian environmentalist Ken Saro-Wiwa, an event that caused an international outcry and Nigeria’s suspension from the Commonwealth.

Saro-Wiwa and eight others had been convicted on trumped-up murder charges after he led a series of mass protests against the pollution caused by Shell’s oil operations in Ogoniland in south-east Nigeria, forcing the company to eventually withdraw from the area by sheer presence of numbers.

“We had entered into some truly dangerous waters with our campaign even though it was entirely peaceful,” says fellow activist Lazarus Tamana. “Oil is Nigeria’s economic mainstay and the government wanted to issue a warning so that no group would ever dare to do what we had done.”

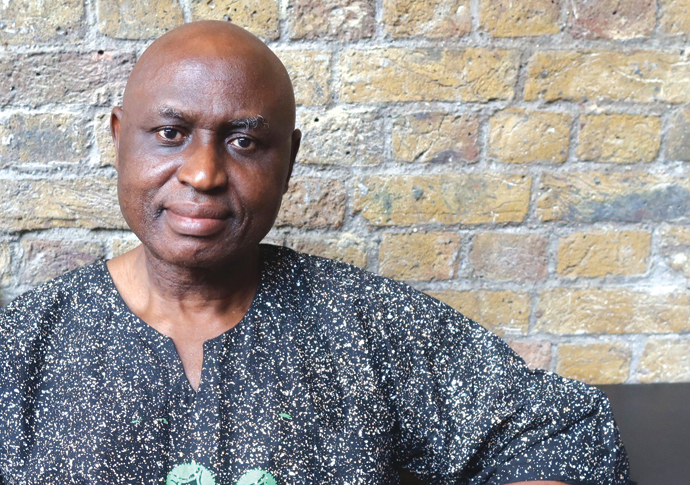

At the time, Lazarus was head of the UK arm of Saro-Wiwa’s Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP), and had been co-ordinating the campaign for the nine’s release. Today he is MOSOP president and I caught up with him during one of his visits to London, taking him back to those dramatic days following the shock arrests by Nigeria’s security forces.

“It was very hard going at first,” recalls Lazarus, who was on Nigeria’s wanted list as a high profile ally of Saro-Wiwa and living in exile. “Amnesty International declared Ken a prisoner of conscience and became one of our campaign partners, so that was helpful.

“And Greenpeace allowed us to distribute our information through their channels. But at the end of the day, we were a tiny group of volunteers, just eight of us, with little money at our disposal and working from our homes.”

But providence intervened in the form of Body Shop founder Anita Roddick, who had already made a name for herself as a human rights activist. “Anita attended a conference in The Hague on indigenous peoples where we happened to have a delegation. When she came back to London she contacted me straight away to offer her support.”

Aside from giving Lazarus and co an office floor with all expenses paid, the late Roddick funded the campaign material, including two films about Ogoniland, a small kingdom in the oil-producing Niger Delta region, and its long-running battle against Shell that were shown on Channel 4.

Lazarus Tamana, president of the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People

“Anita’s coming on board was more than an intervention, it was a rescue package,” declares Lazarus, breaking into a smile. As a result of her many connections, we started to get a lot of media attention. She had a hectic schedule but always attended our demonstrations outside Shell headquarters in Waterloo, which attracted more publicity. She was so dynamic, a great lady, and we shall be eternally grateful to her.”

The Methodist Church was also active in its support, responding to Lazarus’ overtures by sending a delegation to Nigeria’s hardline military leader, Sani Abacha, to plea for clemency.

“Reverend Brian Brown co-ordinated the whole thing and, with the help of the World Council of Churches, they directly approached Shell and the Nigerian government. Abacha turned them away but at least they tried,” he said.

Despite the hard work going on, the campaign ultimately failed to reach the corridors of power. “We approached John Major, Robert Mugabe and Nelson Mandela but they only made strong statements after the event. In fact, there was no international outcry before the hangings and there were few dissenting voices in Nigeria. Wole Soyinka spoke out but most people were afraid.”

The trial at an ad hoc tribunal lasted several months and was deemed to have been a travesty of justice – the burden of proof was reversed and the right of appeal denied. Saro-Wiwa, a popular author and broadcaster in Nigeria, was executed alongside his comrades on November 10 1995, just 10 days after the guilty verdicts were announced.

“That day was one of the most difficult of my life,” Lazarus remembers sadly. “Even though it had been clear the government was not going to back down, I couldn’t believe it had actually happened. However, I had to pull myself together. I spent the whole day going from TV studio to radio station giving interviews and, despite my sorrow, I was left with the determination to continue the fight so that Ken and the others would not have died in vain”

Nigeria became a pariah state as the United Nations, African Union and European Union also weighed in with punitive measures.

“All of sudden, the Ogoni story was known all over the world, and that continues to this day,” says Lazarus, who was able to return to Nigeria in 1999, when civilian rule had been restored.

In 2009 Shell agreed to an out of court settlement of £9.6million after being accused by the relatives of the Ogoni Nine of having collaborated with the military government in their execution, an allegation it denied.

The Anglo Dutch conglomerate has also faced a series of ongoing court claims for reparations over contaminated farmland and fisheries, the main source of local income, although only seven communities have won compensation, with 34 remaining. Next month, as they do every year, thousands of people in Ogoniland will gather to commemorate those hanged with a series of events at which they will renew their collective vow to continue the struggle.

“The battle is far from over,” says Lazarus, a founder of the Ecuador-based pressure group Oil Watch. Although Shell remains locked out of Ogoniland, its ageing pipelines crisscross the area and continue to be responsible for damaging oil spills.

“What is happening to us, is happening all over the Niger Delta. We will continue our campaign to get justice for Ogoniland as well as be a force for change in the whole of the region.”